Every author dreams of making a meaningful connection with their readers. We crave the phrases that make your hearts clench, that stir your deepest fears and unleash your wildest hopes. What is the point of reading if not to FEEL? As a reader, I feel deeply. As an author, I strive to make my readers feel deeply, too, but communicating a meaningful observation about the human experience is not just a matter of heart–it’s a question of writing craft.

While there are many aspects of writing craft that help the reader connect with a story–voice, clarity, and meter, to name a few–today I’d like to discuss truth, and how delivering a story that rings true entices the reader to fall in love. Our hearts seek truth. In life, that’s our common goal: truth in purpose, in love, and in legacy. Without truth our victories ring hollow and our accomplishments feel thin.

The same is true of stories.

Truth in fiction requires all the complexity and nuance of life. If we leave our stories less than fully rendered, they cannot deliver the same gut-rending impact of real life events. It is our goal to make our stories connect, but how? In order to generate the sensation of truth in a fictional work, we need many different ingredients of story craft working together to create a semblance of reality. For me, the key components of this reality are specificity (or detail), originality, and complexity.

Specificity

Think of what you ate for breakfast. Say you had an English muffin. It’s easy to dilute your action into a simple expression such as, “I had an English muffin for breakfast,” but that’s not particularly engaging to read, now is it? We know the facts, but only at the summary level. There is nothing specific about this action that compels us to care about what you had for breakfast. Our hearts are not inspired.

If instead, we heard about how chilly the kitchen tiles were beneath your bare feet, and how you sat opposite another place-setting, its plate empty but for a scant coating of dust, we begin to wonder. We’re comforted by the warmth of each buttery bite of English muffin, but we sense an underlying sadness from that empty place. What happened to you? What is your story?

As soon as you have the reader asking questions, you’ve got them. They ask because they care. When the heart is engaged, we can’t help worrying, wondering, and waiting. Our hearts demand answers. In order to give them to your readers, you must first get them to ask the questions by including meaningful detail in each moment of the story. If your moment has no meaningful detail, cut it. We only wish to read that which engages our hearts fully and leaves us turning the pages in search of answers. Meaningful details make a scene come to life. Without them, our story is no more real than a cardboard cutout.

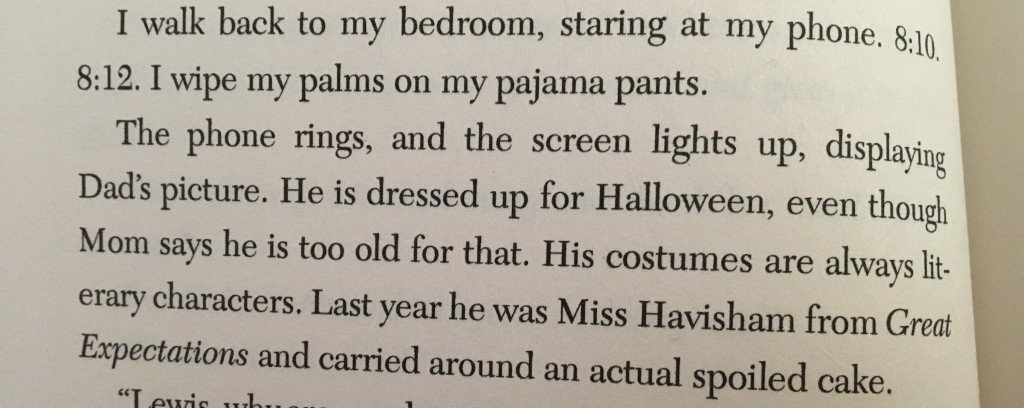

Here’s a wonderful example of detail from Claire Legrand’s Some Kind of Happiness:

These details about Finley’s father give him a specific and very real identity. He is a human being composed of a million odd parts, and here, Legrand gives us one to latch onto. Now we know him, and once known to us, we cannot help but care about him.

Originality

I’ve been reading Cheryl Klein’s amazing writing craft book, The Magic Words, and in it she talks about how important imagination is to a writer’s craft. Imagination is flexibility. It is surrendering oneself to creativity with the full knowledge that you will fail many, many times before you succeed. It is knowing that you will feel pain, frustration, sorrow, and fear from those many failures, and that when the answer comes, it may be with a greater measure of relief than true joy. The imagination is a fickle, dangerous thing. It takes a brave writer to use it, and use it well.

I’ve shared this video from John Cleese many times, but it always warrants sharing again! Have a laugh and a listen. My favorite quote: “Creativity is not a talent; it is a way of operating.”

The first time I listened to this video, I was gobsmacked by Cleese’s underlying message that creativity is a tolerance for failure–literally a tolerance for that twisting, anxious uncertainty that fills your gut when you’re searching for an answer.

The people who generate the most creative answers are very good at getting themselves into a particular mood in order to access their imagination, and then tolerating that awful sensation until they solve the problem at hand. This tolerance is the only thing that will get you to truly unique, original ideas. This matters because ideas that strike the reader as unique also ring with truth.

Ideas that we’ve seen many times before are cliche. They’re stereotypes. They’ve got a negative connotation that’s impossible to shake no matter how strong your voice or meter is. Fresh ideas, however, engage the reader’s imagination. They offer something new, something to understand and learn from–they offer new truths about the world that we have not yet discovered, and there is nothing more exciting for readers than discovery. After all, it is our life’s work to discover the truths of our existence.

Much the same way that detail makes a character or scene come alive, originality allows a premise to flourish in the reader’s mind. An original premise, an original expression of metaphor (see Lindsay Eager’s Hour of the Bees), an original turn of phrase, an original emotional insight, or an original connection to a commonly held belief–these fresh moments enthrall the reader and make it impossible for them to turn away.

Complexity

Let’s go back to that English muffin from this morning. Details allow us to connect with this breakfast in a particularly meaningful way, but we can get even more mileage from this scene if we understand the layers of decision-making that led to it. It’s easy to get caught up in plot and end up with a story that reads A to B to C and so on, but without much real excitement no matter how daring the plot points are. Telling a story is not about describing a sequence of events, but showing your character’s choices as they move through the events.

Did I choose to eat the English muffin even though it’s the last one in the fridge and my husband will likely lose his temper and possibly strangle me for it? That’s a much more important breakfast than before. Similarly, if eating the English muffin reminds me of someone I’ve lost but I do it anyway, my choice is a mix of joy and pain, which is both contradictory and true.

Choices ARE messy. They don’t happen in an instant–even in an instant, half a dozen thoughts can tear through a character’s mind. Their choices aren’t simple. They’re complex. The reader needs to SEE this complexity in order to feel the character’s truth, because no human makes quick, clean choices and no character should either.

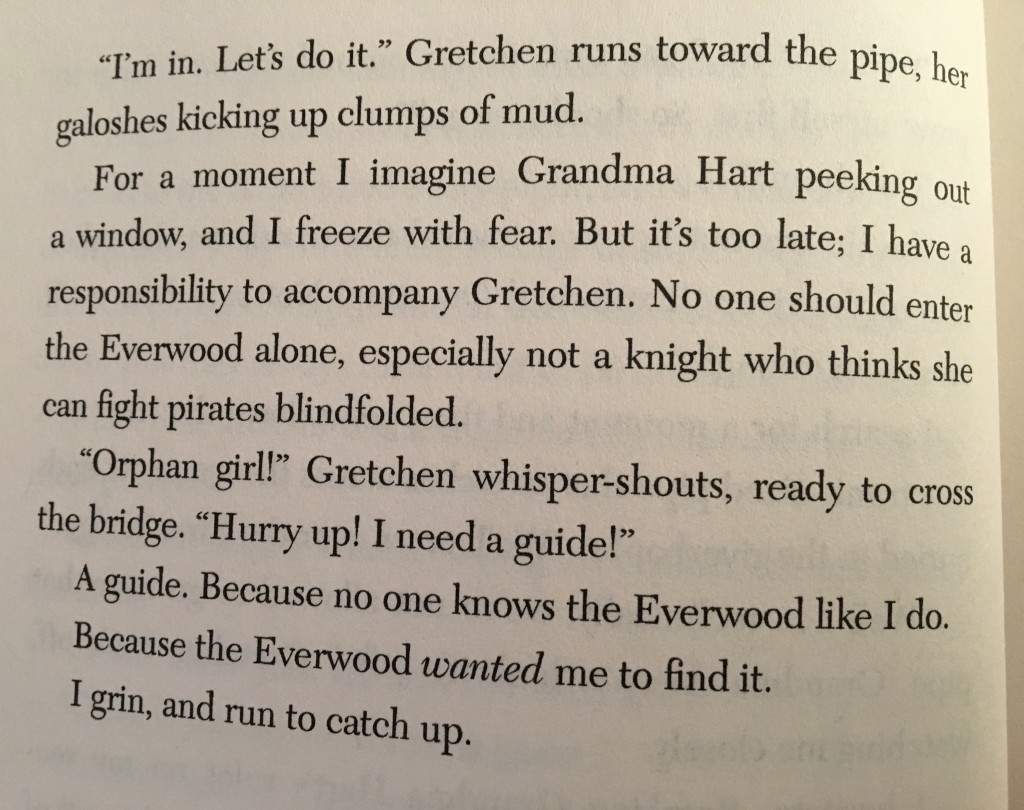

Here’s another example from Some Kind of Happiness:

Here, we see Finley’s full range of reasoning as she decides whether or not to visit the Everwood, the imaginary forest that has become real at her grandparent’s home, and is 100% off-limits. Finley doesn’t hide her thoughts from us. She confesses. She shares her deepest secrets. We see her worries about getting caught for breaking the rules. We see her concern for her cousin. We see her burgeoning desire to be someone needed and loved purely for what makes her unique. These truths all feed into her decision, and by showing them to us, Legrand wins our hearts.

My favorite rule of thumb to generate complexity within a character’s choices is to follow this pattern of decision-making:

First, the character feels. Then they think of their options. They anticipate what might happen if they make the wrong choice (or the right one). And finally, they make their decision.

This doesn’t mean that we need to see each of these steps with each choice our character makes–that would result in a novel far too long and tedious to capture anyone’s heart! Instead, pick the KEY moments. Where does your character need to reveal a deep fear? A wild hope? A secret desire? Allow us to peek behind the curtain of your character’s choices and we will feel the warm blush of a friend sharing a secret.

When a character trusts us, we care for them. We root for them.

We love them.

Leave a Reply